dr Shadi Ghadban

dr Shadi Ghadban

Typology and Composition of the traditional Palestinian House

1. INTRODUCTION

The traditional architecture in Palestine has been developed as the fruit of interaction between the general Middle Eastern concepts and the specific character of Palestine. This interaction has produced very strong expression on the vernacular level where people respond directly to the existing environment (A'rraf, 1985).

Land was the main source of livelihood and status, with very limited transactions with the regional or world market. The Palestinian community retained a system of agricultural subsistence, employing simple agricultural technology. The village as a whole and not the individual was considered the unit of taxation by the state, the community had patriarchal households, the extended family acting as the main unit of production and consumption and labour was divided along clear gender lines (A'miry, 1986).

By the turn of this century, the Palestinian built space experienced dramatic transformations in the socio-economic conditions as well as the cultural values of the Palestinian society. The simplest form of the dwelling house -the shepherd's house has been transformed into new patterns of housing dwellings: peasant's house, village house, isolated residences and the relatively luxurious dwellings of the upper classes. A chain of interdependent structural transformations involving privatization of the land tenure, changes in the organization of the agricultural labour process, marginalisation of agricultural activities, emigration of male family members and nucleisation of the extended land has brought about the critical changes in the existing patterns of spatial relations.

All these changes have proved that architectural systems, i.e., new methods of constructions, the use of new building materials and the adaptation of new building forms, would not be appreciated by the traditional Palestinian peasant society, unless this society was exposed to external forces that operated to undermine the conditions of its existence both at the socio-cultural and material levels. These external forces are the Ottoman land reforms and the British colonial policies.

This study will aim to highlight the development of the Palestinian dwelling house during the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries. The reason for limiting the scope of this study to this period is that few houses exist, which was built before nineteenth century and more of them has been extensively restored that they can no more belong to any specific period.

2. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DWELLING HOUSES

The factors that bear upon the development of the traditional dwelling houses in Palestine could be categorized in two main categories as follows:

2:1- Permanent (constant) factors:

2:1:!- Geography: Although Palestinian land has been exposed to many influences as a result of its geographical position, its architecture retains a remarkable character of its own. The influence of the geography can be observed in the adoption of certain types of construction, form, orientation and the arrangement of the houses. The articulation of the plan, elevations, simplicity of masses, the habit of two-story constructions is largely caused by the predominant conditions in the main three geographical zones of the country: the coast, the mountains and the Jordan valley (fig.1).

2:!:2- Geology and Building Materials: Mud is limited to the Jordan valley as a result of its geological conditions. Otherwise the abundance of stone in the whole country offers the opportunity for good masonry construction. Depending on the location either limestone or sandstone are predominant (Ragette, 1974).

The plenty of stone and its continuous use for construction have produced stone-mason's families who passed on their accumulated skills from generation to generation, evolving a mastery and tradition of design in stone that is largely responsible for the homogeneous character of Palestinian architecture (fig.2).

2:1:3- The Climate: The architecture of Palestine is a synthesis between the local conditions and the solid formulas of the philosophy of life, art and design prevailing in the whole Mediterranean region. The massive construction in stone or mud-brick satisfies to large extent the exigencies of the climate. Cross-ventilation is also facilitated by internal windows between the rooms and the central space, which is the coolest space during the hot daytime. The open ends of the central hall are either turned to the north or to the south in order to avoid deep penetration of the sun's rays. Fortunately, the placement of the house parallel to the contour lines of the slope towards the valley makes its face toward the prevailing wind- direction and ensured the desired ventilation.

2:1:4- Socio-Economics:

The religious affiliation of the Palestinian family didn't affect the distribution of house types in Palestine, and it can't be easily deduced from its habitation. The conditions of living either in the mountains or in the plane area were essentially the same for all religious communities and all families adhered to a strong paternalistic structure.

The Islamic influence is very strong in the artistic and architectural forms and details, but there is very little Islamic influence in the planning of the houses. They were simple and straightforward, and that entails the lack of specialized spaces as well as a lack of privacy for the individual.

2:2- Variable (inconstant) factors:

The critical point of disruption in the traditional structural of the Palestinian society was occurred when the following factors came into action:

2:2:1- declining power of the village sheikh: as e result the sheikhdoms lost the status of relatively independent entity. Villages started belonging to a larger unit, and were inevitably tied with centers of powers located outside the scope of their own sheikhdoms. New relations were established with townships around, and that involved the village in national politics.

2:2:2- Changes in land tenure: The Ottoman land reforms (Tanzimat) that aimed to change the communal ownership of land to private ownership started at 1858. Yet, this reforms where fully affected only during the British Mandate. As a result of these reforms the village tax responsibilities (el-'ushur, the tenth) became an individual responsibility, and that leads to the creation of big absentees landlords, and the deprivation of smaller peasants of their lands.

The collapse of the subsistence agricultural system, along with other developments, resulted in the migration of village residents to seek work in urban centers. The village no longer depended primarily upon agriculture as the means of existence, and this weakened the peasant's organic attachment to the land.

2:2:3- Changes in the occupational structure: This process started at the year 1920. Land that was up until then the only source of livelihood for the community was being slowly replaced by other sources of income and status. By that time a large number of the villagers had become government official employees, schoolteachers, policemen or workers in a new lime factory.

3. COMPOSITION AND TYPES OF THE PALESTINIAN TRADITIONAL HOUSE

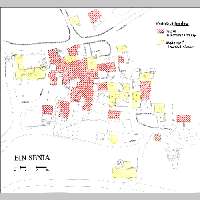

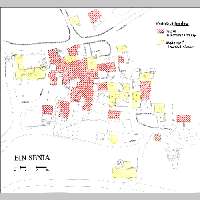

The socio-economic organization of the built environment during the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries was characterized by the implementation of the clustered and concentric patterns of spatial organization (fig. 3). Houses and other structures built in these periods formed the traditional clustered fabric. The house was opened directly to the communal courtyard, it had no direct connection to the outside, it was adjacent to other houses at least from two sides and the back of the structures formed part of the periphery protecting the inner courtyard. This house was built from stone and roofed by the traditional cross vault. Unbuilt grounds between the old structures mainly were used for future expansion. Further analysis of the transformation of the shepherd's house (Initial Model) from 1860 to 1948 showed that the Palestinian traditional house had two sequences of development (fig.4). The first sequence covered the development from 1860 to 1914 when three forms of irregular, regular and composite mass models where prevailing (Revault, 1997). During the second sequence new approaches appeared under the tight interaction of local socio-economic and cultural conditions with Venice and other European centers where new trends had flourished.

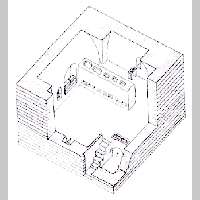

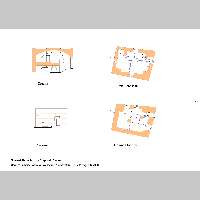

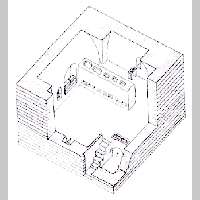

The shepherd's house as basic house had three well-defined and integrated domains (fig. 5,6):

§ The multi-purpose space (Mastabeh - Platform) used by the habitant (fallah).

§ The animal's space (el-rawieh).

§ The agricultural products space (Qa'el-beit).

As far as the building process is concern, it was a spontaneous process depending on reciprocity between members of community. The all members of the extended family carried out the construction process and the gathering of materials. Although the whole community participated in building of the roof (el-a'qdeh).

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the transformations occurred in the socio-economical organization of the built environment was very drastic, and they caused the following developments:

§ Linear patterns of dispersion replaced the clustered and concentric patterns (fig. 7). The village main streets form the basic spines along which houses and other structures spread.

Yet, new structures breaking away from the traditional fabric and new quarters found their way of forming (fig. 8). As a result of all these developments the communal center, containing the plaza, guesthouse, the mosque, and the sheikh's dwellings lost gradually its important function as the focus of communal unity.

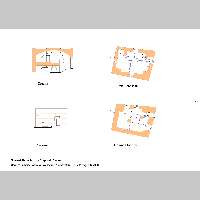

§ Inner spaces of the house have been re-ordered (fig. 9), and the most prominent physical indication was the disappearance of the three mentioned domains. The house built in the period (1920-1950) was left only with the multi -purpose space. Elements such as the fireplace, mud supplies bins, mattres niches disappeared gradually. The acquisition of new items (radios, televisions, refrigerators, gas ovens…etc.) imposed the disposal of all traditional household objects as water jars, kitchen utensils, mud bins, oil lights, mud ovens (taboons)…etc. The new spatial organization of the Palestinian traditional house is shown schematically at (fig.10).

§ Commoditising of the building process. The transformation in the occupational structure and in the kinship relations led to the disintegration of the traditional building team. Hired labour became the prevailing pattern. The master-builder started being hired with his team of paid labourers to execute the building process. The master-builder became the specialist, delegated and authorized to create new forms. Building materials, which were previously extracted directly from the environment, are now brought from the market. This left the community radically unguarded and exposed to the incitement of new building materials and techniques.

§ According with these transformations in the initial model the following categories of houses became popular:

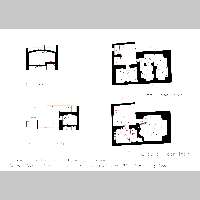

1. The Peasant's house (fig.6).

2. The village house (fig. 11).

3. The isolated house (fig. 12).

4. The luxurious dwellings fig. 13)

4. QUALITIES OF THE PALESTINIAN TRADITIONAL HOUSE

4:1- Color and texture: The color and texture of the natural stone contribute to the homogeneous and organic character of the architecture in Palestine. The stone finishing reveals an intimate knowledge of the material, acquired by generations of stonemasons. Finishes range from rock-faced, with or without tooled margin, to pointed, crandalled or bush-hammered finish. The types of masonry vary with the importance of the work, from polygonal dry rubble masonry to extensively cut ashlar work.

However, within the same building the basic type of masonry will not change in scale or in order of ranging. But it differentiates in surface and jointing.

The color of the masonry follows the limited palette of the nature ranging from yellowish sandstone with hues of red and brown to all possible shades of gray limestone. The predominant roofs are from bleached earth above cross vaults, while vividly red tiled roof contrasts with the skylines of the hills.

The use of color for decorative effects is limited for few elements at entrances, windows, arches… etc. Palestinian architecture is more restrained in this regard than Arab architecture in general, where structural clarity is sometimes masked by the decorations.

4:2- Scale, Massing and Space: The prismatic simplicity of the traditional house, massing of single houses as well as groups of houses and the adherence to a uniform scale are the basic means creating full harmony between house and landscape, house and house or village and landscape.

The juxtaposition of houses creates a repetitive rhythm of mass and void that covers the land without destroying its relief. The cross vault or red tile roofs don't disturb the prismatic clarity of houses since complicated rooftops and definite eaves are avoided.

The human scale is maintained in the traditional architecture. The principal masses, as masonry works, automatically introduce a clear overall definition of scale. Yet every gate, door, window or arch is dimensioned in reasonable relation to necessity and importance. A predominant building rarely disturbs the fabric. Important buildings such as workshops, serails or palaces don't appear as overpowering manifestations but rather as distinguished firsts among equals. Mosques and churches merge with the surrounding community, and can be picked out by their minaret or belfry.

Therefore, modesty and restraint are the key qualities of traditional Palestinian architecture, and they reflect a social structure in which individual or corporate wealth is not explicitly displayed to the outside world. The rooms with four or more meters height have in general lofty proportions, but they retain a human scale provided that the furniture emphasizes the lower parts of the walls and the floors.

4:3- Proportion, Rhythm and Form: The shapes of walls and roofs normally adhere to the simple geometry of squares, rectangles and trapezoids. Spans and cantilevers are strictly limited. The repetitions of similarly shaped openings reinforce continuity and their irregular distributions within one elevation sometimes create pleasant diversity.

Still symmetrical compositions prevail, but such symmetry is never artificially applied from the outside. It is always in harmony with the internal arrangement of spaces, which in turns follows the module of construction dictated by the cross vault spans or length of steel or timber elements. The grouping of windows and arcades creates Strong rhythmic effects.

Considering the tectonic composition of multi-floor construction, the usual practice of building non-vaulted floors on top of vaulted ones, and the general tendency to have fewer openings on the ground floor than on the upper floor, produces an appropriate decrease of massiveness that satisfies the inherent sense of stability.

5-CONCLUSIONS

The composition and typology of the traditional Palestinian house since 1850 to 1948, presented in this study show that this house is a product of a simple and frugal society creating its habitat with elementary means, but utmost with understanding of the functional requirements and the potential of the materials available.

The artistic quality of the dwelling houses created in the nineteenth century was not dependent upon imported models. The stylistic self-sufficiency of the country's architecture has been expressed through the numerous variations of convincing, locally rooted traditions, as well as a great mastery of a craft.

The house was built with the participation of the whole family. People were unaware of new possibilities for development and they accepted what they had without endeavoring anything else.

The Palestinian traditional house occupies its place naturally and without pretension. It is imbedded in a landscape humanized by countless terraces, and built of the materials furnished by the environment. The balance of massing and the harmony of forms were exemplary, and the arrangement of the houses reflects deep understanding of the environment, and is indicative of a remarkable social balance.

Finally, the anonymous dwelling is the unconscious expression of the people's culture. It reflects the needs, desires and living habits of a time, because they are the direct results of the interaction between the human being and his environment.

REFERENCES:

1. A'rraf, Shukri. "The Arabic Palestinian Village- Building and Land Use", Society of Arab Studies, Jerusalem, 1985.

2. A'mery, Su'ad. "Space, Kinship and Gender: The Social Dimension of the Peasant Architecture in Palestine", Ph.D. Thesis, Edinburg University, 1986.

3. Ragette, Friedrich. "Architecture in Lebanon- The Lebanese House during the 18th and the 19th Centuries", American University of Beirut, Lebanon, 1974.

4. Revault, Philippe and others. "Maisons de Bethlehem", Maisonneuve & Larose, Paris, 1997.

5. Badawy, Alfred. "Architecture in Ancient Egypt and the Near East", M.I.T. Press, 1966.

6. Rapporot, Amos. "House Form and Culture", Prentice Hall, London, 1966.

7. A'miry. Su'ad and Tamari, Vera. "The Palestinian Village Home", London, The trustee of the British Museum, 1989.

Za povečavo kliknite na sliko

Click on picture to enlarge

fig. 1 fig. 1

|

fig. 1 fig. 1

|

fig. 2 fig. 2

|

fig. 3 fig. 3

|

fig. 3 fig. 3

|

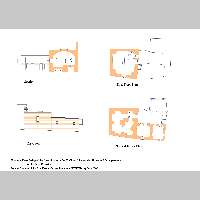

fig. 4 fig. 4

|

fig. 5 fig. 5

|

fig. 6 fig. 6

|

fig. 7 fig. 7

|

fig. 8 fig. 8

|

fig. 9 fig. 9

|

fig. 10 fig. 10

|

fig. 11 fig. 11

|

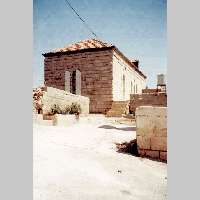

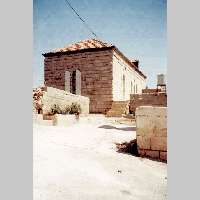

fig. 12 fig. 12

|

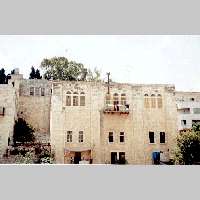

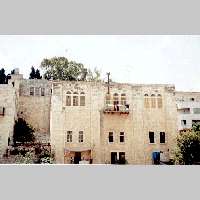

fig. 13 fig. 13

|

fig. 1

Palestinian Urban Landscape

fig. 2

Stone as a Main Building Material

fig. 3

Traditional Patterns of Spatial Organization

Source: Author, Birzeit University and Riwaq

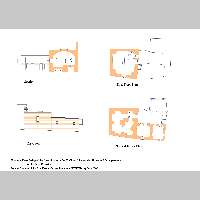

fig. 4

The development of Palestinian house up to 1948

Source: Revault, Ph., Santelli S., author and others - 1997

fig. 5

Isometric View in the Traditional Shepherd's House (Initial Model)

Source: Summer School on Vernacular Architecture, BZU/ Riwaq, July 2000

fig. 6

Example of Shepard's House

Source: Summer School on Vernacular Architecture, BZU/ Riwaq, July 2000

fig. 7

Linear Pattern of Functional and Mass Treatment

fig. 8

New Quarters Breaking Away from the Traditional Fabric

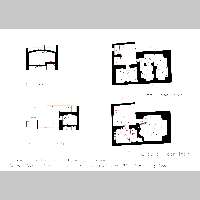

fig. 9

Re-ordering in the Inner Spaces in the Traditional Palestinian House and the Disapperance of the three Domain

Source: Summer School on Vernacular Architecture, BZU/ Riwaq, July 2000

fig. 10

The New Spatial Organization of the Palestinian Traditional House

fig. 11

The traditional Village Court House

Source: Summer School on Vernacular Architecture, BZU/ Riwaq, July 2000

fig. 12

Isolated Dwelling Houses

fig. 13

Luxurious Dwelling Houses