Trans-Manchurian Express

Beijing 26th August - Moscow 1st September 2000

It helps to know you're on the right train ...

There's something about railway stations that has always appealed to me. Of course, like parliaments, railway stations are not subordinated to mere functionalism, at least not major stations. They're intended to make a statement, to have an impact on impressionable visitors. Sometimes this is done through their setting, such as Waverley Station in Edinburgh; few people arriving for the first time in Edinburgh by train forget the memorable moment when, reaching the crest of the rise from the subterranean main concourse, they are confronted by the splendour of the castle, the Bank of Scotland building and Princes Street Gardens which suddenly appears before them. Turning around, they face the vivid North Bridge and the neo-Gothic glory of the Scotsman building, with moody Arthur's Seat as the backdrop.

Other stations achieve the same effect through their design. Kuala Lumpur station's quixotic blend of European and Islamic architecture, Grand Central's sheer bulk and bustle accurately reflects its New York home, and St Pancras is an example of Victorian decoration and extravagance at its best.

Beijing main railway station is no different. It too makes a conscious statement, and reflects its home. Its vast cavernous hall indicates the sheer size of its homeland and capital city. Its marbled floors suggest opulence, conveying the message that all is well in Cathay. And its ultra-modern information panels indicate the high-tech future which the powers that be would like to bring to fruition. It is also a microcosm of its home city, Beijing. From the very moment you first set eyes on it, the teeming hustle and bustle leaps out at you, drawing you inexorably into its midst. The huge plaza giving on to the impressive, modernistic yet distinctly Chinese main entrance to the station swarms with thousands of people coming, going, or camping out for a long wait. This mass of people is then funnelled into the inadequate entranceway, where progress is further slowed by the necessity of putting luggage through airport-style x-ray machines; foreign backpackers however appear to be exempt from this requirement. The huge, high-ceilinged concourse leads to four escalators, always busy, which in turn lead to an enormous corridor lined with miniature shops selling the same things and a series of enormous waiting rooms.

Luckily for us we were travelling first class, an indulgence rendered necessary by the fact that the second-class sleepers were sold out when we bought our tickets in Hong Kong. However, shopping around meant that we got first class tickets for less than some agencies were charging for second class. On the Russian trains which ply the Trans-Manchurian route, first-class carriages are essentially the same as second class, but with one key difference: each cabin has only two berths instead of four.

Another advantage of first-class travel from Beijing is that there are separate waiting rooms. Having spent and inordinate amount of time in bus and train stations perched awkwardly on uncomfortable hard plastic seats bolted together and usually leaning at an angle requiring constant posterior adjustment, and often threatening to collapse entirely at the slightest provocation, it was with great glee and delight that we found ourselves sitting in spacious, soft leather armchairs in an air-conditioned lounge. We played cards and read to pass the time, with occasional trips to the shops to buy provisions for the lengthy journey which awaited us, during one of which I provided great amusement to the staff of one store by trying to determine whether the white liquid contents of a plastic bottle were in fact milk. Having failed to communicate orally in our various mutually incomprehensible languages, I resorted to the tried and tested albeit somewhat embarrassing method of gesticulation and articulation. After mooing repeatedly, squeezing my non-existent udders and persuading the bemused-but-friendly Chinese lady that I was not a complete lunatic, I was in turn confused myself when she seemed to shake her head and nod simultaneously while pointing to her knee. Several repetitions and blank stares later, she eventually managed to pass on the information that it was in fact baby formula and thus ill-suited for being added to coffee. I left and returned for further purchases several times, no doubt further adding to the deep-seated conviction held by many Chinese that foreigners are crazy.

Beijing main railway station

In a strange twist, my search for information regarding our train led me to the discovery that no-one in the foreigners' ticket office actually spoke English, but questioning looks, repeated "Moscow?s" and plentiful smiles elucidated a friendly gestured response.

Back in the waiting room, the Russians had arrived - a mountain of cardboard boxes and jute bags stuffed to capacity surrounded by a small group of blond men and women speaking a language I almost but not quite understood convinced me of this. As the departure time of the Moscow train drew nearer, the character and ethnic make-up of the people changed, boisterous Russians and tired, slightly run-down looking backpackers slowly eclipsing the immaculate Chinese. Twenty minutes before the train was due to leave, a smiling Chinese woman approached us and suggested we board our train, not two minutes after a PSB guard had told me that the train she wanted us to board was definitely not going to Moscow. This was it, we were finally on our way.

Massively overloaded (but not so much so as the Russians) with luggage and provisions, we struggled onto the train and found the charming little cubicle that was to be our home for the next six and a half days. Veronika immediately took charge and set about arranging our luggage in a practical, accessible manner. Then, not long after the train started moving, we were brought our bed linen and we made our beds. A late-night meal of bananas and instant noodles was followed by a brief reading session and merciful sleep.

While on night trains in Thailand, where your are roused from your slumber shortly after dawn and told to get out of bed, our train was amazingly quiet, and we didn't wake up until after 9 the next morning. At this point we discovered another advantage of first-class travel - half the number of people sharing the toilet means (almost) no queuing.

We spent the first full day on the train alternating between reading and gazing out at the scenery which, truth be told, was nothing special - rapid industrialisation has taken its toll on the charm of much of north-eastern China. In the evening we paid our first visit to the hub of social life on the train, the restaurant car. There we met four Germans from Munich and drank a few beers with them. After the restaurant car closed early (8 o'clock), we retired to their cabin to drink some more beer as well as some foul firewater from China named Mao Tai - lethal stuff. Also at the impromptu party was a young Chinese woman and her teenage son, who we called Mama and Little Wu; Mama Wu seemed determined to outdrink us all, something she achieved with alacrity. We were woken at just after four in the morning by our friendly provodnitsa, who presented us with a departure card as we were approaching the Chinese-Russian border at Manzhouli (Manchuria).

Despite the early hour, the station was alive, people, Russian and Chinese, milling about, and the vendors were doing a roaring trade. I bought some sweets and some peanuts with almost the last of our Yuan, and after a couple of hours delay we were past the border formalities on the Chinese side and on our way to Mother Russia.

On arrival at Zabaikalsk, on the Russian side of the border, we were expecting to be allowed off the train, but that didn't happen for about three hours. First the immigration officer came in, speaking excellent English but with enough of the sly officious bureaucrat about him to make me nervous. Leaving China had been a very pleasant, friendly encounter - the Chinese official even asked us if we would mind posing for a photograph with him for a potential appearance on a magazine cover. The Russian side, however, was different; not unfriendly per se, but suspicious enough to put you ill at ease, a tactic presumably mastered during the Col War and never quite shaken off. The immigra5tion check was followed by a seemingly interminable delay before the customs officer came in. She in turn was suspicious when I declared my computer, and insisted on seeing it for herself. Fortunately though, much to my relief, she didn't ask me for the 1500 roubles I was carrying, although taking roubles out of the country is technically illegal, so presumably brining them into Russia must also be flying pretty close to the wind. Another wait ensued, rendered all the more uncomfortable by the uncertainty and a rising need to go to the toilet, which was of course locked all this time. After some time, a striking woman in camouflage uniform instructed us to leave the cabin while she searched it. This was an interesting procedure, as she opened the ceiling of the cabin and carefully searched all the possible nooks and crannies of the room, but seemed completely uninterested in the contents of our rucksacks, lending the whole process a slightly surreal edge of detailed superficiality. In the meantime, the sound of footsteps on the roof indicated the presence of soldiers there searching for something. Yet another delay followed before our passports were taken and we were ordered off the train. Russian trains run on tracks that are somewhat wider than those elsewhere, and this meant that the bogies had to be changed at the border. I had wanted to watch this in action, but everything was done in a vast hangar-type building, out of sight of prying eyes.

While we were waiting, Veronika was continually approached and asked in Russian variously what the time was, where the toilets were, when the bank would be open and so on. Her high Slavic cheekbones, blonde hair and blue eyes led everyone to the obvious yet erroneous conclusion that she was Russian. Many confused expressions on the part of her questioners evinced the bemusement following our stumbling replies.

Finally, several hours late, we were allowed back on board the train, where our passports were returned to us and we went to sleep at last, tired from being roused from our sleep too early. Our Siberian adventure was at last beginning in earnest.

The human landscape changed dramatically as we crossed the border, and the natural landscape to, but to a lesser extent. There was no mistaking now that we were in Russia.

Leaving Zabaikalsk, we came onto a vast grassy plain, flat as a pancake as far as the eye could see, bleak, desolate, empty, eerily beautiful. Late in the afternoon, as the sun was setting, and as Veronika slept peacefully, we were treated to the spectacular sight of a triple rainbow, fog rolling gently over the low horizon adding to the magical quality of the scene. Our provodnitsa, having taken over from her dour, gruff but sometimes friendly male colleague, emerged from her room and proclaimed "Eto krasnaya, da?" to general agreement, at least from those of us who understood her. The Chinese for the most part continued to state silently out of the window at the amazing vision before them.

Irkutsk

Having gazed dumbstruck at the rainbow until it faded with the setting sun, I went off to the restaurant car in search of some light entertainment (read: beer). There I met Simon and Thomas, an English drama teacher and an American nuclear physicist, who were enjoying their beers and trying in good spirits (lubricated no doubt by alcohol) to communicate with three Russians drinking at the next table. Since I spoke at least some Russian, I ended up as an interpreter, which given the dire state of my Russian, was a hard but rewarding task.

We were later joined by Veronika and the Munich four (Eva, Bettina, Udo and Berndt), and we spent a very pleasant evening in slightly inebriated discussion.

At one point Sergei, from Irkutsk, a garrulous hulk of a man, wanted to communicate with the Germans, and my services were once again called upon. He wanted to explain that his grandfather had been killed by the Germans at Leningrad, and I was initially fearful that this was a prelude to a potentially dangerous anti-German diatribe. However, Sergei continued by explaining that he personally had no bad feelings against Germans, a sentiment that was heightened when Berndt explained that his grandfather too had been killed in Russia during the war; hearty handshakes and warm smiles were exchanged.

At one point we toasted the submariners of the Kursk, drowned at the bottom of the Barents Sea. This was not however an introduction to a period of maudlin reflection - save for a passing comment "Putin, bad", it was not to be. Politics again reared its head when we explained where Slovenia was - "Yugoslavia good, Russians, Yugoslavs, brothers". Aleksander, the waiter in the restaurant car, was well-informed enough to be able to list all the ex-Yu countries, and Natasha had even been to Belgrade an Split. Sometimes it pays to be from Yugoslavia, although it can also cause problems, such as our encounter with a student in Beijing who, on discovering that we were from ex-Yu, proclaimed, much to our discomfort, that Milosevic was a great man.

One other highlight of the evening was Natasha's questioning of Thomas' marital status, with a view to becoming his second wife.

Next morning we woke up in time for a fifteen minute stop at Petrovski Zavod, where we bought some pastries filled with potatoes, cabbage, meat and sausage - excellent. We ate a few until the next stop, Ulan Ude, where we bought some delicious kefir, basically sour milk, which I used to drink regularly in Poland - delicious. We then got back on the train after a few photos and awaited our arrival at the legendary Lake Baikal.

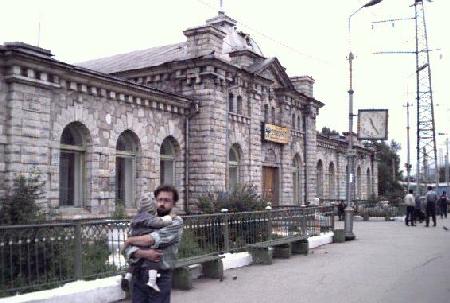

Slyudyanka station

As we approached Baikal, fog set in so that we couldn't see much of the lake, but there were some charming views of headlands. Our next stop was Slyudyanka, apparently a very small village with a delightful stone-built station and an equally delightful brightly painted wooden building, the stationmaster's house, behind it. As we emerged from the train, we were accosted by hordes of women and children selling Baikal fish. We opted instead for pierozhki po sibirski, filled with potato and dill. They were actually very good, but as usual a bit greasy.

Next stop was Irkutsk, where the station had a distinct Mitteleuropa feel to it, grand neo-classical and garishly coloured. We could have been in eastern Europe but for the large number of Asian faces.

From Irkutsk we travelled through vast deciduous forests shrouded in mist with the only signs of human life being the occasional wood-house village presenting a very Russian rural scene. The houses were usually multi-coloured and well maintained, with wooden fences around each. At this point I finally figured out the system indicating the distance from Moscow. Every hundred metres there is a small black and white concrete post on the ground, and every kilometre there is a metal sign hanging from the posts.

In the evening we joined Simon, Thomas, Bettina, Eva, Udo and Berndt. Simon was feeling the effects of the vodka he'd drunk with Sergei et al, and no amount of arm-twisting could convince him to partake. We drank a few beers until we were thrown out of the restaurant car, supposedly because the waiter wanted to go to sleep. We went off to one of the cabins to continue drinking for a while in what was rapidly becoming a nightly ritual. After a while, I wanted to go back to our cabin to get something, and to do so I had to go through the restaurant car. There, the waiter had not actually gone to sleep but was instead watching a pornographic film with his friends!

That night I did not sleep well, primarily because I had a dry mouth because of the vodka. I kept on drinking water and having to go to the toilet.

At Krasnoyarsk we had a twenty-minute stop, so we nipped into the main station to pick up a stodgy microwaved pizza which was actually surprisingly tasty. By this stage we had lost track of time. Russian trains all run on Moscow time, so in all the stations the clocks show Moscow time, not local time, and it was a constant struggle to figure out what time zone we were in, or the approximate time of arrival at our next stop. This was where the kilometre markers by the side of the tracks came in handy.

That afternoon we slept a little, read a little and generally didn't do very much. We continued taking photos of each station we stopped at, and were constantly surprised by the diversity of architectural styles on display. Somehow I had expected all the stations to be drearily similar.

In the evening we once again congregated in the dining car, this time to play cards as well as drink beer. The waiter seemed to be operating in a time zone entirely of his own devising, closing the bar and throwing us out earlier every night.

At Novosibirsk we bade farewell to Thomas, our American physicist, and went to sleep.

The next morning continued as before - breakfast of coffee, bread and Russian sausage, which was surprisingly good. Early in the morning we stopped at Omsk, site of Dostoevsky's exile, although I was still asleep at this point.

This was followed by Nazyvaevskaya, Ishim, an afternoon nap and Tyumen, the first actual ugly station we'd seen. After leaving Tyumen, we finished our bread and sausage, leaving us four hours until our next refuelling stop, Yekaterinburg (Sverdlovsk), site of the murder of the Romanovs in 1917.

From Yekaterinburg, after 40 kilometres we crossed the border between Asia and Europe, which is marked by a white obelisk. We toasted our return to our home continent with a bottle of Sovietskaya Shampanskoe which, although not exactly cold, was pleasant albeit a little sweet for my taste. We continued in the best Trans-Siberian traditions by drinking more beer, then a bottle of vodka until, horror of horrors, we had drunk the bar dry. Perhaps due to our smiling drunken attempts at speaking Russian, the waiter cracked open a bottle of Nasha Vodka and treated us to a few drinks. He was obviously used to Westerners marking the Asia-Europe crossing, as he instinctively knew why we had wanted the champagne and even opened it for us at the right time.

After a poor night's sleep, we stopped at Shariya for fifteen minutes, where we hoped to buy something for breakfast. Unfortunately all that was for sale were bucketloads of wild berries, so we breakfasted on crackers, just about all that was left of our supplies. After that we snoozed until the time came for the penultimate stop at Danilov, where we managed to find some snacks to eat to avoid eating in the overly expensive restaurant car, where, despite the abundant choice listed on the menu, the selection was extremely limited to say the least.

Our final stop was Yaroslavl, which is a large, uninteresting industrial town. As we approached Moscow we passed Sergiev Posad, home to one of the most holy monasteries in all of Russia, and where we were treated to our first half-decent view of the classic Russian onion domes.