|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Professor Dr Franc Gubensek | |||||||||||||

| Dr Dusan Kordis | |||||||||||||

by Dusan Kordis and Franc Gubensek

Ammodytin L is a myotoxic Ser49

phospholipase A2 (PLA2) homologue, which is tissue specifically

expressed in the venom glands of Vipera ammodytes. The complete

DNA sequence of the gene and its 5' and 3' flanking regions has

been determined. The gene consists of five exons separated by

four introns. Comparative analysis of the ammodytin L and ammodytoxin

C genes shows that all intron and flanking sequences are considerably

more conserved (93-97 %) than the mature protein-coding exons.

The pattern of nucleotide substitutions in protein-coding exons

is not random but occurs preferentially on the first and the second

positions of codons, which suggests positive Darwinian evolution

for a new function. A Ruminantia specific ART-2 retroposon, recently

recognised as a 5'-truncated Bov-B long interspersed repeated

DNA (LINE) sequence, was identified in the fourth intron of both

genes. This result suggests that ammodytin L and ammodytoxin C

genes are derived by duplication of a common ancestral gene. The

phylogenetic distribution of Bov-B LINE among vertebrate classes

shows that, in addition to the Ruminantia, it is limited to Viperidae

snakes (Vipera ammodytes, Vipera palaestinae, Echis coloratus,

Bothrops alternatus, Trimeresurus flavoviridis and Trimeresurus

gramineus). The copy number of the 3' end of Bov-B LINE in the

Vipera ammodytes genome is between 62 000 and 75 000. The absence

of Bov-B LINE at orthologous positions in other snake PLA2 genes

indicates that its retrotransposition in the V. ammodytes PLA2

gene locus has occurred quite recently, about 5 My ago. The amplification

of Bov-B LINEs in snakes may have occurred before the divergence

of the Viperinae and Crotalinae subfamilies. Due to its wide distribution

in Viperidae snakes, it may be a valuable phylogenetic marker.

The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree shows two clusters of truncated

Bov-B LINE, a Bovidae and a snake cluster, indicating an early

horizontal transfer of this transposable element.

Keywords : ammodytin L, Bov-B long interspersed repeated DNA,

ART-2 retroposon, Viperidae, molecular evolution.

| Igor Krizaj, Ph.D, Natasa Vucemilo B.Sc and Alenka Eopie B.Sc |

|

During evolution many snake

venom phospholipases A2 (PLA2) [1] have acquired different physiological

activities, including presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotoxicity,

myotoxicity, blood-clotting activity, blood-pressure-depressing

activity [2], several of which can be present in a single species.

In the long-nosed viper (Vipera ammodytes), at least five different

PLA2 are present [3]. Ammodytin L (amd L) is the only natural

mutant of the group II PLA2, in which the active site Asp49, responsible

for the binding of Ca2+, is replaced by serine [4]. The ammodytoxin

C (amtx C) gene [5] has the same structure as other known mammalian

group II PLA2 genes [6] having 5 exons and 4 introns but differs

in structure from PLA2 genes of Crotalinae species [7, 8] all

of which show up to 90 % similarity in intron and flanking sequences.

In the ammodytoxin C gene, the highly conserved ART-2 retroposon

was found in its fourth intron [9]. This unusual occurrence was

explained by horizontal transfer of this transposable element

between vertebrate classes, a tick being a possible carrier. The

possible origin of ART-2 retroposon was erroneously ascribed to

U5 snRNA on the basis of incorrect GenBank data. The MUSUR5E sequence

[10] bears no relation to any other authentic U5 snRNA and could

have been reverse transcribed from contaminating bovine DNA [11].

At that time ART-2 (truncated Bov-B LINE) was still believed to

be a short interspersed repeated DNA (SINE), posing the problem

of how such a short, non-coding element could amplify in a newly

invaded genome [12]. The discovery of the Bov-B LINE in V. ammodytes

and other snake genomes is of considerable interest because this

provides the first evidence of horizontal relationships of LINEs

in vertebrates [9, 12].

ART-2 retroposons were independently discovered in Bovidae genomes

by Duncan [13] and Majewska et al. [14] and designated as ART-2

and Pst repetitive elements, respectively. Lenstra et al. [15]

renamed these repeats as Bov-B SINE elements. Here we use the

originally proposed term ART-2 retroposon when we refer to previous

work. Jobse et al. [16] studied the history of the Bov-B SINE

elements by comparative hybridisation and PCR, and found that

they emerged just after the divergence of the Camelidae and the

true ruminants. Recently, Modi et al. [17] used Southern blot

hybridisation and fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) to

study the distribution of ART-2 retroposon in 46 species of artiodactyls,

and found that it is specific for all pecoran ruminants (fam.

Bovidae, Antilocapridae, Cervidae and Giraffidae). From both articles

it is clear that Bov-B SINEs have been found only in suborder

Ruminantia. FISH studies indicated that the ART-2 retroposons

are fairly evenly distributed among GTG-light and GTG-dark bands

and that this arrangement probably existed in the common ancestor

to pecoran ruminants.

Szemraj et al. [18] described a family of bovine 3.1-kb repetitive

sequences called the bovine dimer-driven family (BDDF), which

contains the complete ART-2 sequence at its 3' end. BDDF members

are mutated or truncated LINE-like elements encoding their own

reverse transcriptase. Szemraj proposed that the ART-2 retroposons

should be considered as truncated BDDF (LINE-like) elements. Copy

number estimates of the ART-2 retroposon in the bovine genome

range from 50 000 [14] to 200 000 [17] copies/genome.

Here we present the complete structure of ammodytin L gene and

observation of the distribution of truncated Bov-B LINE elements

in the genomes of other Viperidae snakes.

Screening of V. ammodytes genomic library. A V. ammodytes genomic library in the l GEM-12 [5] was screened with the ammodytin L cDNA [19] labeled with [35S] dCTP[S] by the random-priming method [20] using the plaque hybridisation method. Hybridisation was carried out at 42oC for 20 h in a mixture of 6 x NaCl/Cit (NaCl/Cit is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 5 x Denhardt's solution, 0.5 % SDS and denatured herring sperm DNA at 100 ?g/ml in 50% formamide. The filters were washed successively with 6 x NaCl/Cit and 2 x NaCl/Cit at 35 oC for 20 min each. The positive clones were rescreened by the same procedure.

|

| Fig.1 Complete nucleotide sequence (A) and the structure (B) of the ammodytin L gene. The deduced amino acid sequence is presented below the coding parts of the exons. Splicing signals, signal for polyadenylation and direct repeats are underlined, exons are in bold capitals. Introns and both flanking regions are designated by small letters. Truncated Bov-B LINE, previously designated as ART-2 retroposon and positioned between direct repeats, is designated by capitals. The structure of the ammodytin L gene is compared with its cDNA. Five exons are indicated by boxes, the four introns and both flanking regions by lines. |

Characterisation of genomic clones. Phage DNA was prepared

from plate lysates [20] and digested with BamHI, EcoRI, SacI and

XhoI restriction enzymes. The resulting fragments were separated

by gel electrophoresis on 0.7 % agarose, transferred to Hybond-N

membranes (Amersham) and hybridised with the amd L cDNA probe

at 42oC as described above. Positive genomic fragments were subcloned

into pUC 19 (Pharmacia) and further digested with different restriction

enzymes. PstI and PstI-AvaI fragments were subcloned into pUC

19 by standard ligation and transformation techniques, using Escherichia

coli host strain DH 5a. Plasmid DNA was isolated by the method

of Sal et al. [21].

Copy number of truncated Bov-B LINE elements in V. ammodytes genome.

A V. ammodytes genomic library [5] was screened with the 628-bp

PstI fragment of ammodytin L gene containing the truncated Bov-B

LINE sequence, labeled with 32P by the random-priming method [20]

using the plaque-hybridisation method. Hybridisation conditions

were the same as described above.

DNA sequencing and analysis. Sequencing was carried out using

the dideoxy chain-termination method [22] with a T7 sequencing

kit following the supplier's protocol (Pharmacia). The nucleotide

sequence of both DNA strands was determined. Analysis of DNA sequences

was performed with the BLAST program [23] at NCBI. Nucleotide

sequences were cross-compared using the program CLUSTAL W [24].

Genomic DNA preparation and Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNA

was isolated from members of several vertebrate classes and an

invertebrate (tick) using standard procedures [20]. 10 ?g of PstI-digested

genomic DNA of each species was separated electrophoretically

in 1 % agarose gel and transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham),

according to the supplier's recommendations. Membranes were hybridised

under the same conditions, as described above, with the probe

used for copy-number determination of truncated Bov-B LINE elements.

The final high-stringency wash was with 0.1 x NaCl/Cit plus 0.1

% SDS at 75oC.

Phylogenetic relationship of Bov-B LINE elements. Snake and some

Bovidae truncated Bov-B LINEs (cut to maximal overlapping length)

were aligned with the program CLUSTAL W [24]. Analyses were performed

on 500 alignment positions. Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed

by the neighbor-joining method [25], with the Kimura two-parameter

model of distances, using program MEGA [26]. Tree reliability

was assessed by the bootstrap method, with 1000 replications using

program MEGA[26].

Isolation and sequencing of

ammodytin L genomic clone. The clone l 2.3, containing a 12.5-kb

insert, was isolated by screening the V. ammodytes genomic library

with a cDNA probe encoding the entire ammodytin L. It was characterised

by restriction analysis using BamHI, EcoRI, SacI and XhoI and

all possible combinations of pairs of these enzymes. After Southern

blot analysis, the positive genomic fragment carrying the complete

amd L gene was subcloned into the pUC 19 vector. It was further

digested with several restriction endonucleases. Only the PstI

and PstI-AvaI fragments, having the most suitable size, were subcloned

into pUC 19 for sequencing. The sequencing of larger segments,

containing introns, was completed using synthetic internal oligonucleotide

primers.

Structural organization of the ammodytin L gene. The complete

ammodytin L gene was found in a 3056 bp DNA segment (Fig 1A).

Alignment of the amd L cDNA and the genomic sequence demonstrates

that the amd L gene consists of a 5' flanking region followed

by 5 exons and 4 introns and a 3' flanking region (Fig 1b). Exon

1 encodes most of the 5'-UTR, exon 2 encodes the signal peptide

up to position -3, exons 3 to 5 encode the protein residues -3

to 42, 42 to 76 and 76 to 122 with the 3'-UTR, respectively. The

four introns of the amd L gene are located in positions homologous

to those occupied by the introns of the ammodytoxin C gene [5],

Crotalinae PLA2 genes [7, 8] and related mammalian group II PLA2

genes [6]. Within the coding region, introns B and D interrupt

the reading frame in phase I, and the intron C in phase II. The

5'-donor and 3'-acceptor splice sites in each of the introns conform

to the GT/AG rule [27]. The DNA sequences of all exons of the

ammodytin L gene are in agreement with the earlier published cDNA

sequence [19], except for 30 bp missing at the beginning of the

5' UTR of amd L cDNA in the latter sequence.

|

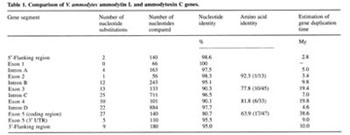

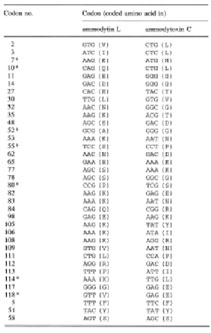

Comparison of the ammodytin L gene with the ammodytoxin C gene.

The sizes and nucleotide sequences of all four introns show a

high degree of conservation in both genes (Table 1) as well as

in other known PLA2 genes from the Crotalinae subfamily [5]. The

splice-site-encoded amino acids in the amd L gene are the same

as in the amtx C gene. The first two exons encoding the 5' UTR

and signal peptide are the most conserved exons in both genes.

Corresponding exons in each gene have the same size. The exons

coding for mature protein are much more divergent, especially

at the amino acid level. The high level of sequence identity of

the introns, the conservation of both flanking and untranslated

regions, and identical positions of truncated Bov-B LINEs in both

genes indicate that the latter are likely to have arisen by duplication

and divergence of a common ancestral gene. The pattern of nucleotide

substitutions in the coding regions, with most of the nucleotide

changes accounting for amino acid substitutions (Table 2), is

very unusual and indicates that these genes are under strong positive

Darwinian selection. The same was observed in Crotalinae PLA2

genes [7, 8]. Changes in protein-coding regions provided the snake

with a new pharmacological activity, which could increase the

effectiveness of the venom. The efficient mechanism of diversification

found in the PLA2 multigene family may have been needed to allow

rapid adaptation of the snakes for defense and for predation of

a wide spectrum of different prey - insects, fishes, amphibians,

reptiles and mammals.

|

| Table 2. Nucleotide and amino acid (in parentheses) sequence differences between ammodytin L and ammodytoxin C mature protein coding regions. The last three codons (5, 51, 58) represent the only silent mutations. Asterisks denote the radical amino acid replacements, all other replacements are conservative |

Bov-B LINE elements in V. ammodytes PLA2 genes. Comparison of

highly conserved intron sequences of Viperidae venom PLA2 genes

[5, 7, 8] revealed that ammodytin L and ammodytoxin C genes contain,

in the fourth intron, a 630-bp long sequence which has not been

found in PLA2 genes of other Viperidae species. The sequence is

75 % identical to the consensus ART-2 retroposon sequence (accession

no. X82879) and shows approximately the same degree of similarity

to numerous ART-2 retroposons or truncated Bov-B LINE elements

from cattle (Bos taurus), goat (Capra hircus), sheep (Ovis aries)

and water buffalo (Bubalus arnee). Such a high level of similarity

undoubtedly shows their common evolutionary origin. The lengths

of the transposable elements in both PLA2 genes are almost the

same, they occur in the same position and differ in sequence by

only 2.4 %. An alignment of the truncated Bov-B LINE sequence

from the ammodytin L gene with that from ammodytoxin C, with the

consensus ART-2 sequence and with two shorter Bov-B LINE fragments

(283 and 288 bp long) found in the third intron of the TATA-box

binding protein (TBBP) genes in Trimeresurus flavoviridis and

Trimeresurus gramineus [28], is shown in Fig. 2. The sequences

from the three Viperidae species are nearly 90 % identical. The

finding of Bov-B LINE elements in T. flavoviridis and T. gramineus

genomes indicates that, in addition to ruminants, they may be

spread in Viperidae genomes.

|

| Fig. 2 Comparison of the truncated Bov-B LINE from amd L gene with that of amtx C gene, ART-2 consensus sequence (accession no. X82879) and related sequences from TATA -box binding protein (TBBP) genes from Trimeresurus flavoviridis (Tfl) and T. gramineus (Tgr). Alignment was constructed with the program Clustal W. The asterisks represent the nucleotides conserved between all sequences. |

The copy number of truncated Bov-B LINE elements in V. ammodytes

genome. Southern blot analysis has shown that truncated Bov-B

LINE elements are highly repeated in the V. ammodytes genome (Fig.

3). Their copy number was estimated by screening a l GEM-12 genomic

library with 32P-labeled truncated Bov-B LINE from amd L gene.

25 - 30 % of the plaques were positive. Assuming that the V. ammodytes

genome contains 3 x 109 bp/haploid genome and the average insert

size in l clones is about 12 kb, the copy number of 3' end of

Bov-B LINE elements can be estimated to be between 62 000 and

75 000 copies.

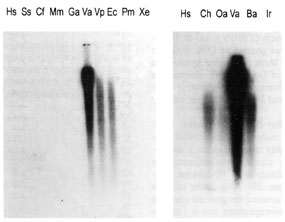

Phylogenetic distribution of Bov-B LINEs. The detection of truncated

Bov-B LINEs in the V. ammodytes genome, in addition to genomes

of ruminants, sheds new light on the present understanding of

the transmission and distribution of LINE elements [9, 12, 29].

Their presence in two vertebrate classes raises the question of

their distribution in other vertebrate classes and of their mode

of transmission between distant phylogenetic taxa. To examine

its possible presence in other vertebrate classes, a Southern

blot analysis was performed, using PstI-digested genomic DNA from

members of classes Mammalia (Homo sapiens, Sus scrofa, Canis familiaris,

Mus musculus and, as a positive control, Ovis aries and Capra

hircus), Aves (chicken Gallus sp.), Reptilia (Vipera ammodytes,

Vipera palaestinae, Echis coloratus, all Viperinae subfamily,

Bothrops alternatus from the Crotalinae subfamily, and Podarcis

muralis from the order Sauria) and Amphibia (Xenopus sp.). An

Arthropoda species (tick Ixodes ricinus), as a possible vector

[9], was also included. As a probe, a 32P-labeled truncated Bov-B

LINE from amd L gene was used.

In addition to V. ammodytes, this LINE was found in the genomes

of Viperinae (V. palaestinae, E. coloratus) and Crotalinae snakes

(B. alternatus, T. flavoviridis and T. gramineus). This may indicate

that its amplification in snakes occurred before the divergence

of Viperinae and Crotalinae subfamilies. The truncated Bov-B LINE

(ART-2 retroposon), originally ascribed to ruminants [13, 17],

has apparently a much wider phylogenetic distribution than previously

thought. The infiltration of Bov-B LINEs into the genomes of the

species examined, in two vertebrate classes, Reptilia and Mammalia,

may have occurred independently at approximately the same time

and presumably also by a common vector. Southern blot analysis

has also shown that in the Mammalia which tested, similar sequences

are not present outside the Bovidae family, neither are they present

in chicken, lizard, frog and tick genomes. Smit [12], in his recent

review, suggests that the invasion of Bov-B LINE elements has

occurred about 30 million years ago in the ruminant genome.

|

| Fig. 3 Phylogenetic distribution of truncated Bov-B LINE elements. Southern blot of PstI-digested genomic DNA from the members of different vertebrate classes and an invertebrate (tick) was hybridised with 32P labeled ART-2 probe. Genomic DNA samples from the following species were analyzed : human, Hs (Homo sapiens); pig, Ss (Sus scrofa); dog, Cf (Canis familiaris); mouse, Mm (Mus musculus); chicken, Ga (Gallus sp.); long-nosed viper, Va (Vipera ammodytes); Palestinian viper, Vp (Vipera palaestinae); Ec (Echis coloratus); Pm (Podarcis muralis); Xe (Xenopus sp.); goat, Ch (Capra hircus); sheep, Oa (Ovis aries); Ba (Bothrops alternatus); and a tick, Ir (Ixodes ricinus). |

Truncated Bov-B LINE elements in the V. ammodytes PLA2 gene locus

are very young. In order to estimate the time of integration of

the truncated Bov-B LINEs into V. ammodytes PLA2 gene locus, we

examined their distribution in several species of the Viperidae

family by Southern blot hybridisation and sequencing of V. ammodytes

PLA2 genes [30]. The low degree of divergence between truncated

Bov-B LINE elements and their limited presence in the fourth intron

of amtx C and amd L genes in V. ammodytes, but not in the orthologous

loci of other snake species, where they are abundant in the genomes,

indicates that retrotransposition into both PLA2 genes has occurred

very recently but before the gene duplication leading to amd L

and amtx C genes.

It is well known that recombination and/or gene conversion can

create situations where distinct regions of the same gene (exons,

introns, transposable elements) may have different evolutionary

histories. Because evolutionary rates differ significantly between

introns and exons (Table 1) in both PLA2 genes, this raises the

question as to which part of the gene can be used to infer divergence

times in the case of genes evolving under positive Darwinian selection.

From calculations of the divergence times of particular regions

in both genes (Table 1), it is evident that in the genes evolving

under positive Darwinian selection, the conserved introns may

be useful for the estimation of the age of duplicated genes. The

time of the insertion of the LINE in both PLA2 genes is estimated

at 4.8 My ago, using a 0.5 % nucleotide substitution/My [31].

This estimate is within the average range of time 6.5 My, inferred

from the intron and both flanking regions.

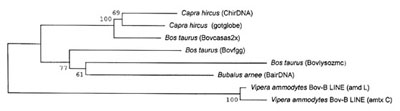

Phylogenetic relationships of Bov-B LINE elements. To clarify

the phylogenetic relationships between snake and Bovidae Bov-B

LINEs, we first aligned some sequences (Fig. 4) and then constructed

a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining method [25] shown

in Fig. 5 where two distinct clusters, the Bovidae and Serpentes,

clearly separated. The grouping of these LINE elements from different

species or different genes from the same species is supported

with the high bootstrapping values as shown in Fig. 5.

Sequence analysis of the B. taurus Bov-B LINE elements (data not

shown) indicates that they belong to subfamilies of different

evolutionary ages, as has been observed for many other LINE elements

[32]. The V. ammodytes and B. taurus sequences display a degree

of similarity only slightly less than that displayed by the highly

divergent Bov-B LINE subfamilies in the bovine genome (75-95 %).

The transposable elements found in species that belong to different

genera, families, orders, classes and even kingdoms, may sometimes

be very similar. Such similarities are generally restricted to

a small part or parts of the nucleotide or protein sequences,

but are much greater than might be expected for species so distant

phylogenetically [33]. By contrast, the similarity of the truncated

Bov-B LINE elements among V. ammodytes and Bovidae is not restricted

to a small part of the nucleotide sequence, but is distributed

throughout the whole sequence without any gaps. Its presence in

two vertebrate classes, and the high level of similarity, suggests

that horizontal transfer is the only possible explanation of the

origin of this LINE. It is inconceivable that these sequences

could persist in non-coding regions of mammalian and reptilian

genomes which diverged over 250 My ago and still retain the present

level of similarity, particularly since, in most of the mammalian

LINE elements of different species, the similarity is limited

only to the coding regions, whereas in their 3' UTR, it has disappeared

[29, 34].

Possible carrier of Bov-B LINE elements. Although we proposed

Ixodes as a possible vector for the horizontal transmission of

the ART-2 retroposon between vertebrate classes [9] we did not

obtain any hybridisation signal in the Southern blot analysis

of the Ixodes genomic DNA tested. There are a few possible explanations

for this result. The sequences might be too divergent at the nucleotide

level to be identified by DNA hybridisation techniques, it might

not be present in the Ixodes genome, or Ixodes might not have

been involved in its transmission. As Capy et al. [33] pointed

out, however, it is not necessary for a vector to have the transposable

element integrated in its genome, it can instead operate as a

mechanical vector, as in the case of semiparasitic mite transfer

of the P-element between two Drosophila species [35, 36].

|

| Fig. 5 Phylogenetic relationships between Bov-B LINE elements. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was based on the Clustal W multiple alignment from Fig. 4. To assess the reliability of branching patterns, 1000 bootstrap replications were performed. Numbers at the nodes indicate the bootstrap confidence level as a percentage. Sequence name abbreviations are from Fig. 4. |

LINE and SINE elements use similar mechanisms of retrotransposition,

which is similar to that of the R2 retrotransposon [37]. This

mechanism requires only the sequences at the extreme 3' end of

the RNA transcript, so that 5' truncated elements, which are truncated

Bov-B LINE elements, can still be integrated, and if these truncated

elements are transcribed they can generate new families of repeated

elements in a species. It seems clear that the boundary between

LINE and SINE elements will become more difficult to define in

the future. Bov-B LINE elements and LINE-derived parts of tRNA-SINE

elements [38] are presently the most striking examples of this

difficulty.

Bov-B LINE as a phylogenetic marker. The appearance of the Bov-B

LINE in V. ammodytes and other snake genomes is of considerable

interest because it is the first example of mammalian LINE-specific

elements observed in a species outside the class Mammalia [9].

The defective copies of LINEs, once inserted, appear to remain

stable in the genome of the host [29]. Comparisons between mammalian

b-globin loci have shown that different species can be distinguished

by the pattern of LINE-1 insertions at this site [39]. LINE and

LINE-like sequences have been found in every mammalian genome

studied and in a number of non-mammalian genomes as well, and

are species specific [29, 34]. The insertion of LINE sequences

without doubt affects the genomes, where they cause deletions

or duplications of regions by unequal crossover. Unfortunately,

snakes are among the least studied organisms in genetic terms.

It is thus premature to comment on the mutational impact of Bov-B

LINE elements in the snake genomes. It is possible that their

high copy number in closely related Viperinae and Crotalinae snake

species may have played a role in their speciation, perhaps by

facilitating reproductive isolation, as proposed for LINE-1 elements

in rodents [29].

Acknowledgement. For critical reading of the manuscript we thank

Prof. R. Pain. We are also indebted to Dr A. Smit for his valuable

comments. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and

Technology of Slovenia by grant no.: P3-5243-0106.

| Gregor Anderluh, B.Sc and Loulou Kroon-Zitko, B.Sc |

|

References

1. Dennis,

E. A. (1994) Diversity of group types, regulation, and function

of phospholipase A2. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13057-13060.

2. Kini, M. R. & Evans, H. J. (1989) A model to explain the

pharmacological effects of snake venom phospholipases A2. Toxicon

27, 613-635.

3. Gubensek, F, Ritonja, A., Zupan, J. & Turk, V. (1980) Basic

proteins of Vipera ammodytes venom. Basic studies. Period. Biol.

82, 443-447.

4. Krizaj, I., Bieber, A. L., Ritonja, A. & Guben1ek, F. (1991)

The primary structure of ammodytin L, a myotoxic phospholipase

A2 homologue from Vipera ammodytes venom. Eur. J. Biochem. 202,

1165-1168.

5. Kordis, D. & Gubensek, F. (1996) Ammodytoxin C gene helps

to elucidate the irregular structure of Crotalinae group II phospholipase

A2 genes. Eur. J. Biochem. 240, 83-89.

6. Seilhamer, J. J., Pruzanski, W., Vadas, P., Plant, S., Miller,

J. A., Kloss, J. & Johnson, L. K. (1989) Cloning and recombinant

expression of phospholipase A2 present in rheumatoid arthritic

synovial fluid. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 5335-5338.

7. John, T. R., Smith, L. A. & Kaiser, I. I. (1994) Genomic

sequences encoding the acidic and basic subunits of Mojave toxin

: unusually high sequence identity of non-coding regions. Gene

139, 229-234.

8. Nakashima, K., Nobuhisa, I., Deshimaru, M., Nakai, M., Ogawa,

T., Shimohigashi, Y., Fukumaki, Y., Hattori, M., Sakaki, Y., Hattori,

S. & Ohno, M. (1995) Accelerated evolution in the protein-coding

regions is universal in crotalinae snake venom gland phospholipase

A2 isozyme genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5605-5609.

9. Kordis, D. & Gubensek, F. (1995) Horizontal SINE transfer

between vertebrate classes. Nature Genetics 10, 131-132.

10. Hamada, K., Kumazaki, T., Mizuno, K., & Yokoro, K. (1989)

A small nuclear RNA, U5, can transform cells in vitro. Mol. Cell.

Biol. 9, 4345-56.

11. Lenstra J. A. (1992) Bovine sequences in rodent DNA. Nucleic

Acids Res. 20, 2892.

12. Smit A. F. A (1996) The origin of interspersed repeats in

the human genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6, 743-748.

13. Duncan, C. H. (1987) Novel Alu-type repeats in artiodactyls.

Nucleic Acids Res. 15, 1340.

14. Majewska, K., Szemraj, J., Plucienniczak, G., Jaworski, J.

& Plucienniczak, A. (1988) A new family of dispersed, highly

repetitive sequences in bovine genome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta

949, 119-124.

15. Lenstra, J. A., Van Boxtel, J. A. F., Zwaagstra, K. A. &

Schwerin, M. (1993) Short interspersed nuclear element (SINE)

sequences of the Bovidae. Animal Genet. 24, 33-39.

16. Jobse, C., Buntjer, J. B., Haagsma, N., Breukelman, H. J.,

Beintema, J. J. & Lenstra, J. A. (1995) Evolution and recombination

of bovine DNA repeats. J. Mol. Evol. 41, 277-283.

17. Modi, W. S., Gallagher, D. S. & Womack, J. E. (1996) Evolutionary

histories of highly repeated DNA families among the Artiodactyla

(Mammalia). J. Mol. Evol. 42, 337-349.

18. Szemraj, J., Plucienniczak, G., Jaworski, J. & Plucienniczak,

A. (1995) Bovine Alu-like sequences mediate transposition of a

new site-specific retroelement. Gene 152, 261-264.

19. Pungerear, J., Liang, N. S., ©trukelj, B. & Guben1ek,

F. (1990) Nucleotide sequence of a cDNA encoding ammodytin L.

Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 4601.

20. Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular

Cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd edn, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory,

Cold Spring Harbor NY.

21. Sal, D. G., Manfioletti, G. & Schneider, C. (1988) A one

tube plasmid DNA mini preparation suitable for sequencing. Nucleic

Acids Res. 16, 9878.

22. Sanger, F., Nicklen, S. & Coulson, A. R. (1977) DNA sequencing

with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

74, 5463-5467.

23. Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, E. W. & Lipman, D.

J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215,

403-410.

24. Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. (1994)

CLUSTAL W : improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple

sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific

gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22,

4673-4680.

25. Saitou, N. & Nei, M. (1987) The neighbor-joining method

: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol.

Evol. 4, 406-425.

26. Kumar, S., Tamura, K. & Nei, M. (1994) MEGA : Molecular

evolutionary genetics analysis software for microcomputers. CABIOS

10, 189-191.

27. Senapathy, P., Shapiro, M. B. & Harris, N. L. (1990) Splice

junctions, branch point sites and exons : sequence statistics,

identification and application to genome project. Methods Enzymol.

183, 252-278.

28. Nakashima, K., Nobuhisa, I., Deshimaru, M., Nakai, M., Ogawa,

T., Shimohigashi, Y., Fukumaki, Y., Hattori, M., Sakaki, Y., Hattori,

S. & Ohno, M. (1995) Structures of genes encoding TATA box-binding

proteins from Trimeresurus gramineus and T. flavoviridis snakes.

Gene 152, 209-213.

29. Furano, A. V., & Usdin, K. (1996) DNA "fossils"

and phylogenetic analysis:using L1 (LINE-1, long interspersed

repeated) DNA to determine the evolutionary history of mammals.

J. Biol. Chem 270, 25301-25304.

30. Kordis, D. (1993) The structures of Vipera ammodytes PLA2

genes. PhD Thesis, University of Ljubljana.

31. Li, W-H., Gojobori, T. & Nei, M. (1981) Pseudogenes as

a paradigm of neutral evolution. Nature 292, 237-239.

32. Deininger, P. L., Batzer, M. A., Hutchinson ; III, C. A.,

& Edgell, M. H. (1992) Master genes in mammalian repetitive

DNA amplification. Trends Genet.8, 307-311.

33. Capy, P., Anxolabehere, D. & Langin, T. (1994) The strange

phylogenies of transposable elements : are horizontal transfers

the only explanation ?. Trends Genet. 10, 7-12.

34. Singer, M. & Skowronski, J. (1985) Making sense out of

LINEs : long interspersed repeat sequences in mammalian genomes.

Trends Biochem. Sci. 10, 119-122.

35. Houck, M. A., Clark, J. B., Peterson, K. R. & Kidwell,

M. G. (1991) Possible horizontal transfer of Drosophila genes

by the mite Proctolaelaps regalis. Science 253, 1125-1129.

36. Kidwell, M. G. (1993) Lateral transfer in natural populations

of eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 27, 235-56.

37. Luan, D. D., Korman, M. H., Jakubczak, J. L., & Eickbush,

T. H. (1993) Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a

nick at the chromosomal target site : a mechanism for non-LTR

retrotransposons. Cell 72, 595-605.

38. Ohshima, K., Hamada, M., Terai, Y. & Okada, N. (1996)

The 3' ends of tRNA-derived short interspersed repetitive elements

are derived from the 3' ends of long interspersed repetitive elements.

Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 3756-3764.

39. Hardison, R., & Miller, W. (1993) Use of long sequence

alignments to study the evolution and regulation of mammalian

globin gene cluster. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10, 73-102.